Review by Simon Jenner, September 16 2025

★★★★(★)

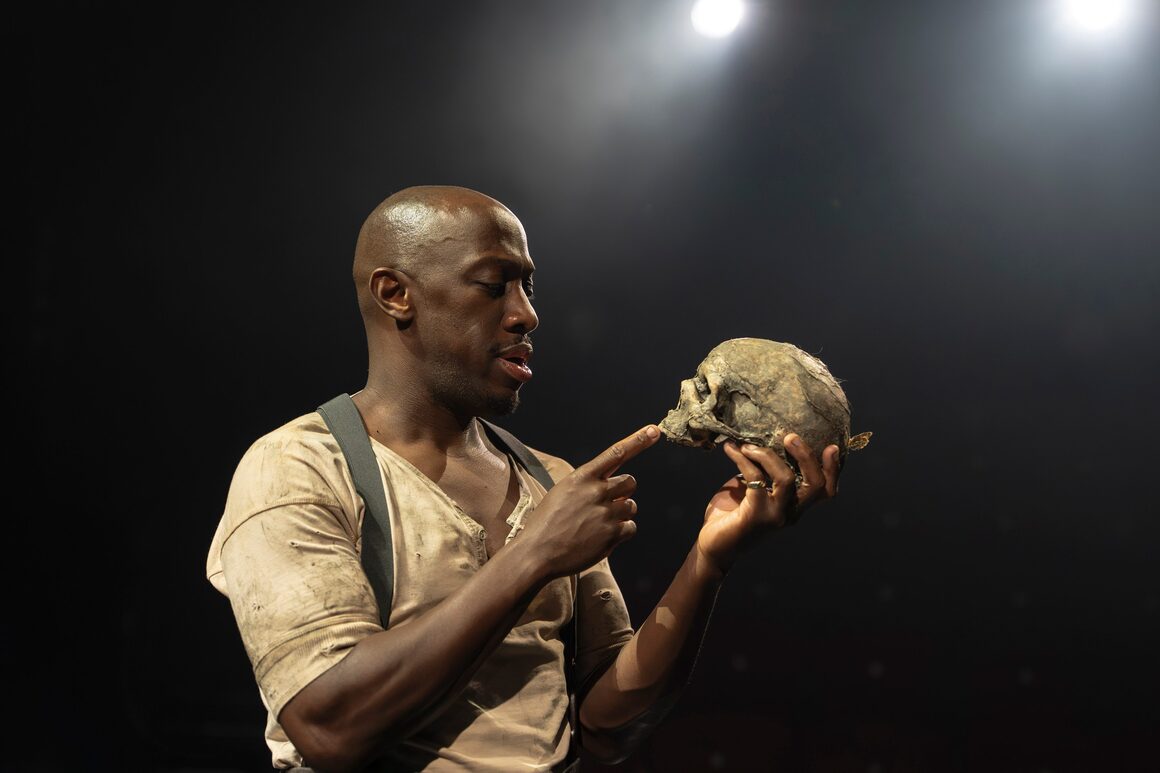

To stage Hamlet in Chichester’s Minerva might seem to bound it in a nutshell; but it takes a king to make infinite space. Happily with Giles Terera in the title role directed by Justin Audibert till October 4, and designed by Lily Arnold, this first ever staging of the play at Chichester does just that. Indeed, this is the most complete Hamlet in many years, coming in at three-and-a-half hours.

The political is highlighted, not with gimmicks like modern surveillance (which can work well) but textual inclusion. There’s impress of soldiers, not just Fortinbras, who march across the raised gallery, in a superb use of Arnold’s raised upstage space. Hamlet’s quizzing of the soldier who provokes a reflection worthy of a First War poet about 20,000 men dying for a patch of untillable ground. The extended gravedigging scene, often cut, is a highlight. Where Terera questions Beatie Edney and Simon Darwen’s Gravediggers after their own comic scene. The flicker of complicity between Horatio as he informs Gertrude secretly of Hamlet’s return, marking her silent divorce from Claudius’ sphere. And there’s illumination too as Horatio and Marcellus semaphore wildly behind Hamlet’s back: which of them is going to break the news about seeing Old Hamlet’s ghost? It’s comic – this production is often funny – but always advances out understanding: of character here as well as plot.

Ariyon Bakare and Giles Terera. Photo Credit: Ellie Kurttz

Despite or because of its length this production goes at pace, with Lucy Cullingford’s movement echoing tohe dispatch ad clarity of words. The production’s also leavened with Jonathan Girling’s sometimes folk-inflected, sometimes more romantic music. There’s brief a capella snatches, and moments when Claudius is alone and begins an incantation. The sacramental and folk scatter world over individuals, so they’re lit from within. Sometimes that light is terrible, with Ariyon Bakare’s superbly realised Claudius: an agonised display of guilt and ruthless improvisation. This is a Claudius of wight and feeling. The only chemistry that lacks is with Gertrude, whilst there’s far more with Laertes, which might suggest Claudius’ comfort zone. As Claudius’ satellite, Keir Charles’ wonderful – not senile – Polonius is brisker early on; so only later do we receive the full otiose diet of his addresses, that worsen with high rank. Each twirl and flourish of speech is calibrated never to quite guy itself. With Laertes they’d been tolerable, the comedy played up as the son keeps trying to leave.

Terera though shows every inch why he should be king. He’s engaging when addressing Geoff Aymer’s very different selves: the fearsomely halo’d Old Hamlet and affable Player King (actors at this point in 18th century garb with Aymer orotund of speech), with Edney’s Player Queen and actors huddling round to patiently hear the prince tell them how to act. Terera is cannily authoritative in this, and deliberately bland when reading out script prior to his tripping advice.

His scenes with Horatio (Sam Swann) are particularly intimate: though Swann plays quiet confidante, a friend who consciously takes flight with others here, where his own authority is less cowled and must speak. He’s particularly good with Nana Amoo-Gottfried’s warm and sensitive Marcellus, more rounded here and a contrast to Darwen’s bluffer Barnardo. Terera stamps his rationale on soliloquies, and the few transpositions of speeches work well.

With Gertrude (Sara Powell), there’s an early moment when Terera’s prince is reluctant to let go of her hand. It isn’t quite followed up, where Powell ‘s Gertrude seems over-awed by her change of king, and suddenly volatile and terrified in the bedroom confrontation, bewildered out of her senses. There isn’t the connection some Gertrudes and Hamlets enjoy, if that’s the word for passionate, almost incestuous exchanges in some readings. The plot sets up their growing alignment, though not the characters.

With Ophelia (Eve Ponsonby) Terera is almost abusive, and Ponsonby – despite Ophelia knowing her father’s eyes are upon her – disinhibited, passionately kissing Hamlet. Earlier, with brother and father she appears playful, though already quite charged. This is an Ophelia already exhibiting a touch of illness that flares up in Act Four. There, having already hinted at pregnancy, she arrives bloodied with miscarriage. Much of Ophelia’s behaviour is luminous and terrible. Ponsonby though isn’t allowed a vulnerability, a trait certainly amplified with blood-loss and multiple trauma. There’s a fierceness that ousts the fragile; we need that too.

Giles Terera and Sara Powell. Photo Credit: Ellie Kurttz

The first half with Terera about to strike Bakare’s Claudius is gripping, absorbing and despite the lack of swords, more headlong than that which follows – and that’s Shakespeare’s fault.

From Act Four Laertes (Ryan Hutton), already making an impression provides most impetus. He’s the finest Laertes I’ve seen: clarion-spoken at need, but adroit in shadowy undercurrents, this Laertes quick to rouse. He’s almost beside himself as violent knockings – the political is at the doors throughout – admit him to confront the king. The brief sword skirmish with Claudius is prelude to the rest, but violent scuffles with Hamlet in between show how the nutshell’s cracking with external pressure. The eddies – Ophelia and Hamlet’s long ruminations with Horatio and the gravediggers – necessarily slow the action, to allow the existential Hamlet to emerge. Here as in Richard Eyre’s words “Hamlet grows up but he grows up dead.”

The dispatching of complicit Rosencrantz (Tim Preston) who knows what’s in that commission, and slightly franker, luckless Guildenstern (Jay Saighal) is slightly less shocking, as Preston’s complicit servility smoothes an apparent plain-speaking northerner with craft. It’s here that David Angland’s oleaginous Osric wafts a courtier’s supercilious disdain, though he doesn’t flourish it the way some do. That’s a courtly contrast to the often-cut figure of Nick Howard-Brown’s Voltemand. He’s early and late the sober ambassador, sole agent of efficiency.

Sobered by his uncle, the formerly brattish Fortinbras (Ozzy Aigbomian, after a frozen Francisco on watch) isn’t a psychopath who murders everyone at the end, but regally dispatches; and accepts Hamlet’s vote and Horatio’s election. The crown starts and ends this play. Some recent Hamlets offer chaos after chaos, as if the rest is silence after massacre. Here, however arbitrary, there’s an orderly close round the circlet.

Beatie Edney and Giles Terera. Photo Credit: Ellie Kurttz

Lit atmospherically by Ryan Day (there’s mists), the stage below is often tenebrously lit with candlelight; the blue chequered floor admits everything from a circular table, often broken into panels: the space uncluttered allowing those sword-fights and skirmishes thrillingly staged by Christian Cardenas. It’s the upstage gallery (side galleries frequently used) that undergoes scenes changes. From a bleak watch, Gertrude’s bedroom, bleak wastes with a mound connecting it to the stage, the royal enclosure, all are studded with character whilst the main stage is swept clean. It’s an inspired use of space.

The National’s Hamlet opens two days before this closes. Audibert’s production though has special claims. It’s the most reasoned and complete traversal of Hamlet I’ve seen live. It absorbs and thrills. It needs no gimmicks to make it new, indeed fresh and wholly different to any recent predecessor. If the tension drops in the second half for some that’s because of Shakespeare’s Act Four; and indeed the normally-deleted material from an already eerily-hushed Act Five. If there’s a slight lack of engagement with some characters, then it’s a decision. Ophelia’s amped-up world involves a charge that can repel empathy if not intimacy: we only need a touch of nature here. Gertrude’s world can bewilder itself, and needs more of that hand-grasp with Hamlet. An outstandingly thought-through Hamlet though, with more of the prince and play in it than I’ve seen. And Terera’s is with the best of recent decades.

Sound Designer Ed Clarke, Movement Director Lucy Cullingford, Fight Director Christian Cardenas, Casting Director Matilda James CDG, Voice & Dialect Coach Stephen Kemble, Assistant Director Becca Chadder, Production Manager John Page, Costume Supervisor Isobel Pellow, WHAM Supervisor Melanie Bouvet, Props Supervisor Sharon Foley, CSM Suzi Blakey, DSM Rob Le Maistre, ASM Roma Radford.