Review by Simon Jenner, February 11 2026

★ ★ ★ ★ (★)

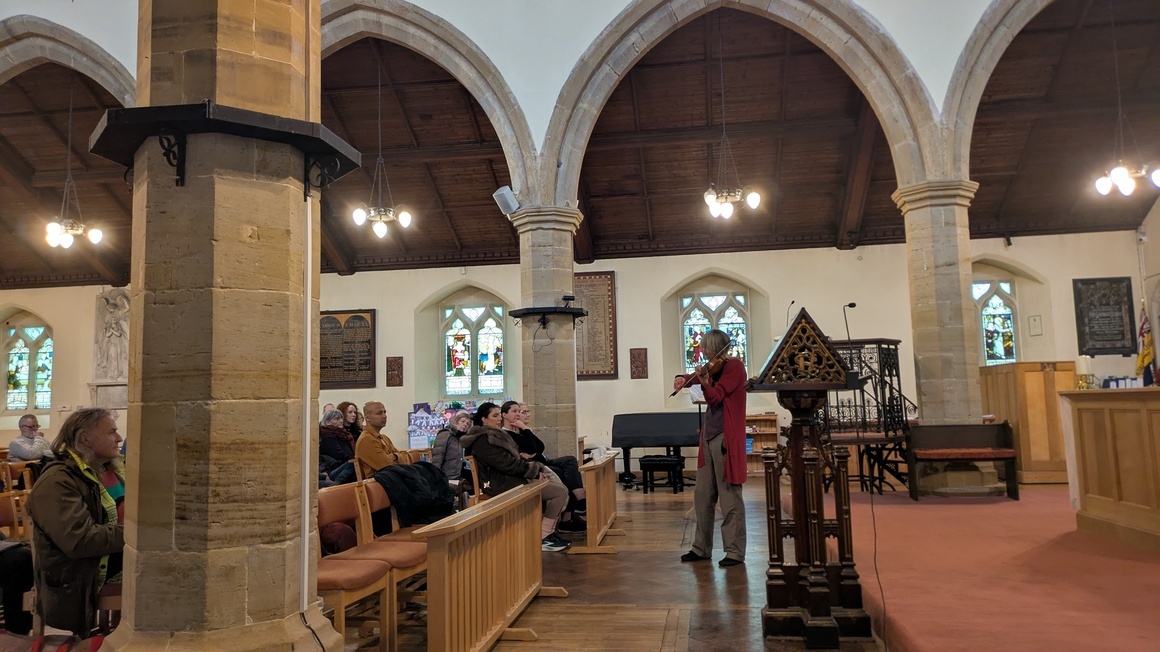

Ellie Blackshaw has been established as a solo and chamber violinist on the south coast for a long time now, since she studied at the RCM. So people take her for granted.

It’s good to hear why though at St Nicholas. Here Blackshaw, unaccompanied performs the whole of Bach’s solo Partita No 2 in D minor BWV 1004; interrupted before its monumental final Chaconne by Hindemith’s solo Violin Sonata Op 31/1 from 1924.

The Bach even here is substantial without the Chaconne which arrives after another journey. Blackshaw shows a clean attacking line in the opening Allemande which she deftly ports over to the ‘running’ Corrente. The following Sarabande is the first heart of the double heart of this work. Blackshaw is both expressive and continually emphasises flow in this searching, (very) slow-dancing music. As she does in the slightly treacherous Gigue which speeds to a provisional conclusion. Had we not known the Chaconne this would have satisfied on its own..

The Hindemith is an enigmatic work from Hindemith’s early maturity. It has two multi movement sections.

The Lebhafte-Langsame-Lebhafte sings with the sweet-bitter tang of later Hindemith but here still expressively long-lined and without the staccato rhythms of some of his later work. Though much solo work is similarly long-breathed. The exploratory nature of the opening statement is interrupted by the rapt Langsame (‘slowly’ but not Adagio) that soothes but doesn’t solve and the questions return. There’s a resolution but not a conclusion.

The post tonal world continues in the Intermezzo-Prestissimo where the Intermezzo really does traverse some blanched expressionist landscape with a purity of line characteristic of all the work. It’s remarkably uncluttered. Hindemith makes up for it with his Prestissimo but even here there’s a muted scramble that’s anything but raucous. More like a frenetic ghost revisiting their grave. Indeed Blackshaw here applied a mute: an innovation that works spectacularly.

There’s something haunted and spectral about this work altogether and Blackshaw’s performance is engrossing. Where else can you hear Hindemith? Well here two weeks ago with a viola sonata. But not often enough.

The Bach Chaconne or Ciaccona suggests the whole work and this movement in particular was composed as a memorial to Bach’s first wife who died and was buried suddenly whilst he was away. As a vast acoustic Escorial it plays out 33 variations in the bass rhythm riding to two climaxes. Blackshaw negotiates it as a work to differentiate in tone. Very high E moments she quietens down to emphasise the spiritual stillness, perhaps grief. Above all though this transcendental work is a slow abstract, a hidden instrumental requiem notwithstanding.

Blackshaw continually negotiates the fluid line. It’s still searing, and heard here (as I once heard Isabel Faust play all the Sonatas and Partitas in this space in 2015) it still captivates. So that anything said seems redundant.

Blackshaw though with her interrogatory musicianship probes corners I’ve not heard before, indicating these variations. Rapt, rare music making.

Photo Credit Simon Jenner