Review by Simon Jenner, August 15 2025

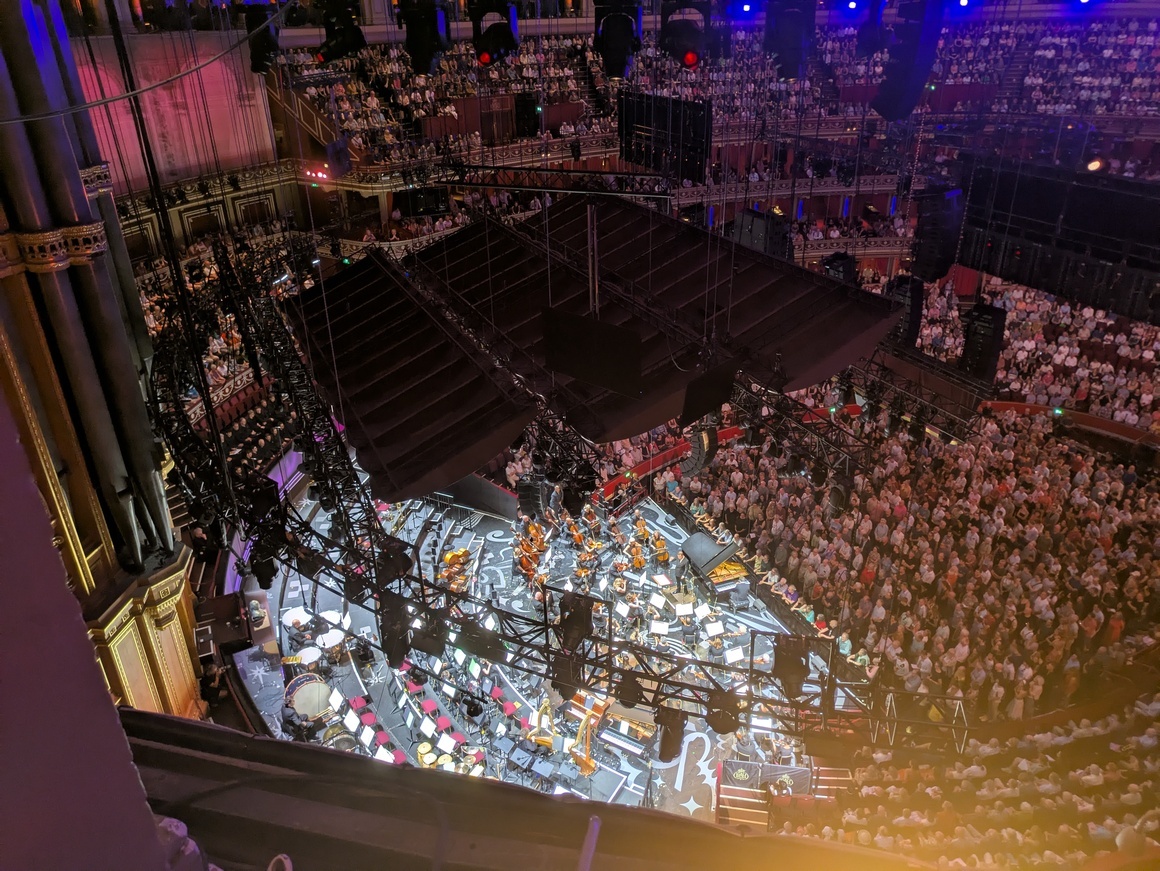

Ryan Bancroft brings BBC National Orchestra & Chorus of Wales, Synergy Vocals, pianist Benjamin Grosvenor and bass-baritone Kostas Smoriginas to this 35th Prom (they’re not numbered any more but hey): a Prom where the chief draw and anniversary composer weren’t the chief interest. With her death at 93 earlier this year, it’s fitting that Sofia Gubaidulina’s represented by at least a short work inserted by a BBC orchestra. Perhaps we can look forward to anniversary performances bigger works like her three violin concertos or symphony: 2031 anyone? Through heritage and inclination, Gubaidulina described herself as “the place where east meets west.”

Her Revue Music (1976), is as unknown as it’s mysterious, as it is full of funk and big band jazz. Nearly starved by not being even able to write film music, Gubaidulina fell on this Music Hall commission. That hall never transpired but this sort of Soviet Rio Grande (without piano, but percussion instead) went on to be used as dance music, and the money helped. After, it was a slow ascent, much helped in the West, paradoxically, by Gubaidulina being banned in the Soviet Union for years. After its fall she moved to Hamburg.

Gubaidulina resembles her colleague Alfred Schnittke (1934-98) here: his ‘polystylism’ isn’t quite Gubaidulina’s deliberate collision of styles, which she keeps separate, though Revue Music too is a thing of wild contrasts. It starts and ends with tubular bells, intoning a sacramental rite, which in a way it is. Bancroft and the BBC NOW) stomp their way deliriously but tight-reined though the jazz moments. The Synergy chorus some in with some unearthly opening and surprising closures. It’s a kind of Russian ‘Neptune’ at this point; though again the only piece that compares is Constant Lambert’s Rio Grande, with its jazzy piano and orchestra suddenly giving way to a chorus singing the Sacheverell Sitwell poem through slow piano ripples. Here, the Synergy choir sing a mystic, star-stung poem of Afanasy Fet (1820-92), Russa’s great poet between Pushkin and Blok. And they – with the bells – have the last word.

There’s less to be said about Ravel’s G Major Piano Concerto (1929-31) and Benjamin Grosvenor’s account. That’s no reflection on the work or soloist. To a degree this is an analytic performance slowed down in the central section of the first movement and particularly slow movement. Grosvenor’s passagework is gorgeous and details are brought out with an occasional frisson. Grosvenor’s prone to this: last year here he managed certain undreamt filigree in a polar opposite work: Busoni’s Piano Concerto.

There are however downsides: the precision Grosvenor brings is perhaps harmed by some of this drawing-out, and rhythmically it can lack bite. The finale reminds me of Constant Lambert (as critic now) rarely criticising Darius Milhaud for a work: “where a host, realising he’s forgotten to put alcohol in the first round of cocktails, puts methylated spirits in the second to make up for it.” There’s some scamper and messiness.

As there is in the generous encore: Prokofiev’s 1943 Sonata No. 7 finale, the one where Glenn Gould suggests it depicts the tank battle of Kursk with lend-lease Shermans. But who cares? It’s an encore and marvellous to see it blown off by Grosvenor: a portent of recording it perhaps.

Bancroft’s Mahler 3 disappointed many, but I only heard it on radio. Again a work perhaps drawn-out. But his traversal of Shostakovich’s Symphony 13 in B flat minor Op 113? This is another matter and the gem of the night.

Shostakovich had capitulated to demands to join the communist Party in 1960, leaving him almost suicidal (String Quartet no. 8, written in the shadow of Dresden), and writing his dreary Symphony No. 12 in D minor “the Year 1917”: like the 5th in key but not nature. All in exchange for finally premiering his “withdrawn” revolutionary Symphony No. 4, from 1936. But inspired by Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s ferocious ‘Babi Yar’ poem raging against the lack of memorial to Jews massacred near Kyiv, Shostakovich “became one of us again” as pianist Maria Yudina (rather unfairly) put it. Shostakovich went on to set four more poems – one of which, ‘Fear’, he asked Yevtushenko to write. It’s one of his very greatest symphonies, and with the 4th, his most revolutionary.

Shostakovich’s great champion Yevgeny Mavrinsky backed out of premiering it. Three soloists dropped out one by one and only when Kiril Konrashin stepped in did the work stand a chance, first heard on December 18,1962. The authorities wanted some of Yevtushenko’s poetry cut or changed (particularly about Soviet anti-Semitism), but Kondrashin stood firm, going on to make a live recording of the second performance before it was more or less banned, despite those slight cuts subsequently made. Ormandy – who made (still) the finest Shostakovich 1 – recorded it, after giving the US premiere.

Ryan Bancroft paces this five-movement, hour-long Symphony (sixty-three minutes here), with an almost bone-crunching force in the percussion of the first, ‘Babi Yar’ poem, and with biting singing. It’s a devastating piece and you can see why Shostakovich originally considered it a stand-alone before adding other poems. Yevtushenko’s scorching, self-searching words self-accusing almost, are his truest legacy.

There’s terrific expressive power here: the irony and sarcasm skirls in the second movement ‘Humour’ which can’t be killed even if executed. The third and fourth poems or movements are linked. ‘In the Store’ commemorates the patient, heroically strong women waiting for bread and intensely moving, as is ‘Fear’, the one Shostakovich asked for, where Soviet SNAFU is ironised: “Fears are dying out in Russia”, when they knew the Thaw would freeze again.

Kostas Smoriginas is both idiomatic and charismatic, with sharp and soulful interjections from the lower-voiced men of the chorus (Chorus-Master Adrian Partington).

The final movement (‘A Career’) in its melodic shape and sparse scoring sounds like the finale of one of Shostakovich’s string quartets of the time, strikingly so in fact. Anything from the 7th to 11th. It’s as naggingly memorable as the best. Instead of strings there’s two flutes, shaped like a quartet arch. The perkily alien theme recurs in different guises. The work (a bit like the Gubaidulina, as well as some Shostakovich) fades to an ethereal celesta and a funereal bell – it tolls for not only Jewish victims, but us, and (one can’t help thinking) for genocidal wars now. It’s not unexpected (indeed not before time) that some chose to programme the 13th. Just when Ukraine is being traded over again, Kyiv bombed, and racial hatred of all kinds breaking out to what seems a final apotheosis. This is a Soviet artist’s reply to such authorities everywhere: and it is just criticism. An outstanding Prom. Catch in on BBC Sounds.

Gubaidulina: Revue Music for Symphony Orchestra and Jazz Band (UK premiere)*

Ravel: Piano Concerto in G

Shostakovich: Symphony No.13 in B-flat minor, Op.113 ‘Babi Yar’

Benjamin Grosvenor (piano)

Kostas Smoriginas (bass-baritone)

BBC National Orchestra & Chorus of Wales (men’s voices)

Synergy Vocals*

Ryan Bancroft