Review by Simon Jenner, June 19 2025

Like Parsifal itself, this is a worthy challenge for Glyndebourne. Musically it’s superlative, steered by conductor Robin Ticciati. Dramatically Jetske Mijnssen’s new production – set around 1882, the year of the premiere – makes a cat’s cradle of complexity. Happily a few strands light up intensely, like filaments of hot wire. Others gleam with a metallic pewter sheen; several snap.

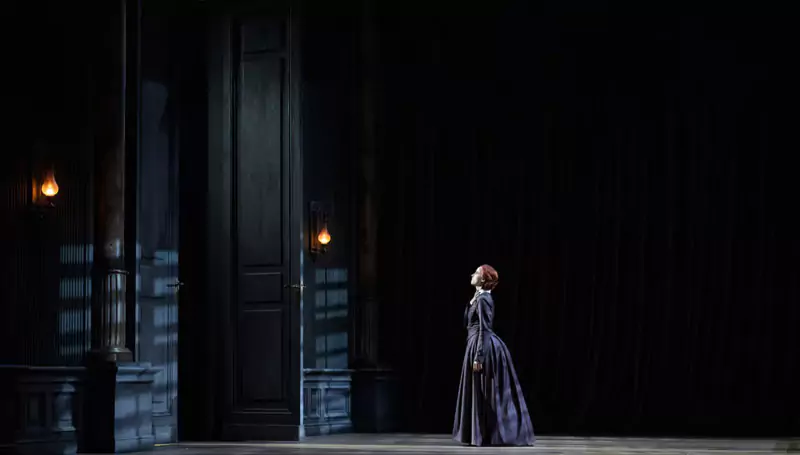

Daniel Johansson as Parsifal and Kristina Stanek as Kundry. Photo Credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Glyndebourne’s founder John Christie wanted to stage Parsifal. It only happened when Tristan und Isolde premiered in 2003, and Meistersingers in 2011. Nikolaus Lehnhoff’s acclaimed Tristan returned in 2023.

Glyndebourne’s acoustics allow the LSO to blossom in Ticciati’s hands: he coaxes the reduced pit strings to glow and ascend. And details: when Kundry’s flying through the air is referenced, a sweep of strings illuminates where Strauss got an idea for his 1896 Don Quixote. There’s tremendous lower brass: stabbing outbursts during Act II’s seductions. Their stertorous cries heighten the psychodrama. Gently skirling winds are pinpointed though Act III, where every chuckle and burr is heard. Then there’s the singing.

The male chorus seem a tenebrous force: often rising black-suited in a mournful choir. The women, often seraphically offstage, are magical. Their

Flower Maidens startle; their almost Bacchanalian swirl round a befuddled Parsifal thrills and disturbs.

An old hand commented: “I don’t know who wrote the third act, but it wasn’t Wagner.” Harsh: the uncut words are carried in clear surtitles by Richard Neel. Though as another opera-goer said, the absence of a spear at the end of Act II is “a cop-out”. Being the most dramatic point of Parsifal the absence of Klingsor’s and his castle’s annihilation might be down to Glyndebourne enforcing a different solution to Bayreuth’s. Nevertheless, it’s part of Mijnssen’s domestic, human-scaled vision.

Mijnssen references Chekhov, 22 at the time. Crucially, there’s no place for Chekhov’s humour. Myth, agon, mysterious figures, the past: Ibsen’s destructive inscape of family better fits Mijnssen’s invocation of Wagner’s domestic experience. Nevertheless even if dead swans might work dragged on by an evening-suited ingenue, spears and imploding castles don’t. Solution: banish them. But you banish their world too.

The design speaks Nordic bleakness (the narrative’s set in Spain; not even Wagner cared about that). Ben Baur’s stark, bleached grey set doubles as sick room and dining room, screens drawn across for variety. A bed of violets erupts where the organ rises in the production of Saul, Fabrice Kebour’s lighting is a sober affair: fining down to candlelit moments: a chiaroscuro of ritual.

Props include a funeral cortege with gleaming black coffin, snow effects at Easter. Gideon Davey’s black costumes alternate with grey for a collection of Kundry dopplegangers: the Flower-Maidens blaze red-headed like her. Dustin Klein’s choreography turns on a circling tread. There’s clarity in Marius Bolten’s dramaturgy: what’s sung can be followed. The why is elusive: Mijnssen unbalances Wagner’s intricate world.

Not least there’s a surtitle novelty: the story of Cain and Abel. It’s suggested Klingsor and Amfortas are brothers who’ve fallen out over immortal wandering Kundry: cursed for laughing at crucified Christ, referencing the Flying Dutchman. The rest is Wagner: Amfortas excludes Klingsor from the brotherhood despite his efforts. The latter builds a magic castle to thwart him; and emasculates himself. It parallels Alberich’s renunciation of love. Previous Wagner themes dovetail in Parsifal. The Act III sickbed echoes Tristan und Isolde. An anti-Tristan opera, it renounces sexual love.

John Tomlinson’s the greatest Gurnemanz of recent times. He’s now miraculous as Titurel, aged father of Amfortas. Tomlinson has the most incisive German; though his voice lacks its old glow, there’s a superb gaunt utterance as Tomlinson transmits sorrow at a wounded son, who fell to Klingsor and Kundry’s enforced lures.

Audun Iversen rises to inject pain into Amfortas’ voice without his baritone being compromised. It’s a fiendish character role, occasionally sung at 45 degrees. Whilst there’s redemptive journeys – literal journeys – for Kundry and even more surprisingly, Klingsor, Iversen’s Amfortas is healed differently. The king’s resurrection, though he gives place to Parsifal, is a release and renewal. Here, just as two others are granted life, Mijnssen references assisted dying as if it were topical. Even here, Amfortas, healed by Parsifal and reconciled to Klingsor, lies tucked in bed, bestrewn by Kundry’s violets. He’s not covered over, as if he still breathes. So there’s ambiguity, anti-climax. Wracked with guilt over his father Titurel’s death Amfortas may be: but if healed, why peg out? It seems another cop-out.

Gurnemanz has to tell the backstory, grip audience and fabric, even logic of the work. He’s also Super-Everyman, baffled by Parsifal but finally accepting. John Relyea makes him believable. His bass voice is darkly heroic, troubled in majesty. There’s an inky magnificence as if he holds up the work’s foundations by voice alone.

Ryan Speedo Green’s Klingsor is burnished, his bass-baritone incisive and menacing, his acting coercive and smouldering, scornful and suave. His mute acting in Act III is a silenced penance, evil purged of itself, with a little stab and counter-menacing from Parsifal.

There’s innovation in mute actors, featured as Young and Old Kundry, the same doubling for Amfortas and Klingsor. And Parsifal’s mother Herzeleide, a mute Lucy Burns who sits and mourns at varying points in Act II as her son avoids seduction by Kundry, who invokes his mother in her kisses. Wagner invented the Parsifal Complex. The most striking doubling is Rosy Sanders’ Old Kundry echoing her younger self, seemingly an old retainer fussing with water-bowls; not Kundry at all. It doesn’t land till you read the programme.

Thus in her despised dual role as messenger and servant, Kundry as “old” and “wild” is unsuspected as the sexy younger woman forced by Klingsor (when away) to seduce every knight. So away from the castle, she’s enslaved again despite her struggles. Klingsor’s magic is too strong.

Kristina Stanek is a clean, cool dramatic mezzo: enforced to a sexual warmth she doesn’t feel. Until, enraged by Parsifal she actually does scorn him and rise to fury – and desire – that he resists her. The drama swirling around the mute mother-figure of Burns is Freudian, even Ibsen-like. Stanek weaves a sometimes warm, sometimes icy circlet of lustre and lust, mezzo-forte commands ringing with frustration. Like Klingsor she’s reprieved, doesn’t feel he need to wither into age but join Parsifal, or look across in the final scene. You hope they’d become an item: the Brotherhood has to be peopled.

Daniel Johansson’s ardent in heldentenor incomprehension: added to which he’s a holy fool. Parsifal starts by dragging in that slaughtered swan, before nearly strangling Kundry. If this is to underscore how a damaged young man deprived of a father and abandoning his mother (so she dies of grief) really is a sociopath, the drama’s off to a good start. That’s reinforced as the male chorus of knights ritually beat Parsifal up: so he lies prone for nearly the rest of the Act. Parsifal would fit in. The only difference is they loved the swan.

Johansson’s voice rings with warmth and affect, lacking the last ounce of cut-through. His voice will mature.

Dramatically Johansson throbs with gentleness. It’s Parsifal transformation Mijnssen wants to underscore. As he seizes on the spear, Parsifal becomes all-compassionate, including for Kundry and Klingsor. That’s the finest point of Mijnssen’s production: it adds to what Parsifal can be. The problem is it jettisons so much else, and that needn’t be the case. An Amfortas healed might release this Parsifal too.

This review first appeared in Plays International & Europe, to whom grateful acknowledgment is made for reproducing it here.

Daniel Johansson as Parsifal and Kristina Stanek as Kundry. Photo Credit: Richard Hubert Smith.