Review by Simon Jenner, July 22 2025

Before he became immersed in screenwriting David Lean films and others up to The Mission, Robert Bolt shot to fame after he expanded a 1954 radio play. Bolt’s A Man For All Seasons from 1960 is revived and directed by Jonathan Church, arriving at Theatre Royal Brighton till July 26th. After a six-month run it transfers briefly to the West End, featuring a superb cast led by Martin Shaw as Sir Thomas More.

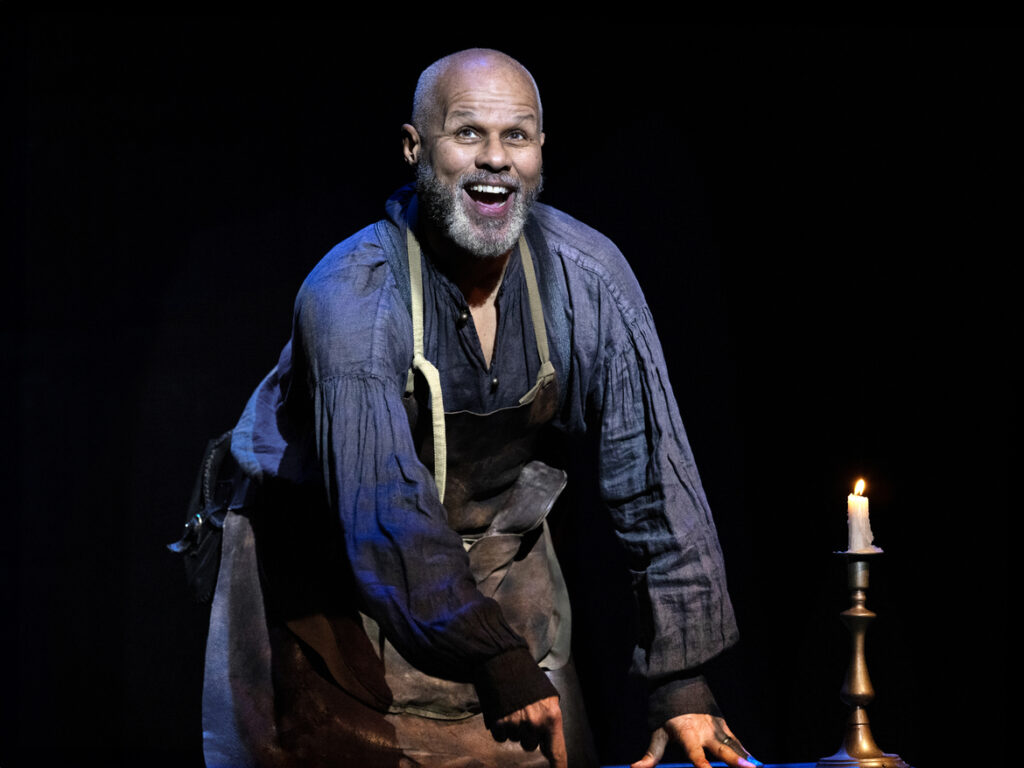

Gary Wilmot. Photo Credit: Simon Annan

It’s theatre’s loss that Bolt only went on to write a couple more plays, notably the historical sister-blister of Mary I and Elizabeth I – Vivat, Vivat Regina, from 1971. It still gets revived, even on Broadway.

Everything speaks quality here, particularly vocally with this cast; there’s not a weak link. Simon Higlett’s magisterial panelled set slides out panels to reveal or occlude a great stone hearth burning in the Mores’ home. At other times, it becomes Cromwell’s office with no hearth, and at others, bare bars form the backdrop, like all warmth and illusion stripped away; at times a blazoning royal regalia drops over proceedings. It’s lit with tenebrous force by Mark Henderson, throwing shadows. Wooden panels, like walls have ears; but here they breathe too. At the opposite end of audibility, Matthew Scott’s music comes in mainly late: striking heraldic trumpets blaze crisp and sharp on this stage. Paul Groothius’ sound does what it can with recorded music.

The time spans nine years 1526-35, with the changes rung in the Mores’ home, as they shamble into genteel poverty. They mark More’s refusal – only implicit, never spoken – to endorse the king’s new self-proclaimed rulership of the Church of England. This is the king “who always loved a man”, particularly More; so, if unconsciously, marked him for destruction. More knows silence in law is construed as consent. Every trap laid for him by Cromwell he’s wily enough to swerve. How can Cromwell either persuade him (which to be fair, he’d prefer) or condemn him? More’s care to avoid every legal pit dug for him is so successful the other characters resort to pantomimic absurdity. The drama arises from this. And the humour. More, famed for his one-liners, is well-served by Bolt.

Gary Wilmot’s The Common Man walks on in a Brechtian stumble to upset the lot, and patters to us throughout, whisking props away in baskets and snatching up books. Wilmot relishes morphing from More’s canny servant Matthew (More enjoys his time-serving nature) to paid informer (he doesn’t want this), to boatman (Henderson’s lighting rippling streaks of emerald dark across a couple of scenes). He conjures epilogues too.

Martin Shaw’s careful, ruminative, occasionally stentorian Sir Thomas More compels with a vocal force often used to purr, which rises to clarion damnation only once or twice. He’s gravitas incarnate, but gentle, and Shaw proves himself as consummate a theatre actor to match any of his famed TV roles.

Shaw’s More from the start shows an amused, light contempt for the slippery, not entirely conscience-free Richard Rich, whom Calum Finlay manages to make look thoroughly uncomfortable, twitching realpolitik till it fits him like an itchy hairshirt under silk; as he sloughs into a snake. More refuses Rich proper employment twice, pronouncing him out of his depth. Bolt’s Rich is a study in resentment and opportunism, scratched by awareness of better natures. More’s final riposte to him brings the house down. Did I say the play’s that funny?

Two characters are superbly realised in just one scene each: a youthful Henry VIIII in Orlando James’ striding and cavorting through More’s home to demonstrate his leg in a dance. His quicksilver bonhomie – darkening to an excuse to leave on being mildly crossed – burls and ripples through the household: a psychopathic force of nature nothing withstands. Except More.

Nicholas Day’s magnificent Cardinal Wolsey similarly stamps his authority on just one scene. His havering manner around More’s conscience is both wily and resigned. Already fingered for destruction, he somehow holds off the inevitable with fragile dignity.

Timothy Watson’s Norfolk, bluff not cerebral, is as much as friend as he can be, even after Thomas pushes him away for his own good. Like The Common Man, this aristocrat only sees good sense in compromise. Watson, baffled by nice points of law and sneered at by Cromwell, barrels mildly; with a touch of the aristo-strut flowered hideously in James’ Henry.

Abigail Cruttenden’s great moment as sidelined wife Alice More comes out at the end: she rises vocally to match her husband in a rapid-fire diction around Shaw’s adamantine speeches. Cruttenden hovers and snipes anxiety throughout. Her Alice glints with hurt as her stepdaughter Margaret holds more sway. Their final explosive scene finally releases feelings simmering all through, threatening till then never to be expressed.

Daughter Margaret More’s part is more ambitious and Rebecca Collingwood’s mix of care and casuistry is palpable. Margaret uses her quick intellect to wield her own education back on her father. Since he taught her, this makes for affecting moments as in lockstep with him she finally breaks with logic to plead humanity. Collingwood’s Margaret also floors clever Henry who tests her fluency in languages, to his discomfort.

Margaret’s intended husband William Roper (Sam Philips) though no match for father or daughter, is more sharply portrayed than I remember as a contrarian hothead: first as a Lutheran, which got him into trouble; then reverting to the Catholic Church. Intemperate and a danger to himself he’s not as shrewd as Margaret. Philips, giving him heat and volubility, humanises a man driven by intellectual passions rather than reason. He’s no fool here, but is ridden by genes, according to More: “They’re a cantankerous lot, the Ropers, always swimming against the stream. Old Roper was the same.”

Edward Bennett’s Thomas Cromwell reminds us of the pre-Hilary Mantel Cromwell: the old serpent, here willing to save More but quite as willing to let the King see his death. Bennett makes him plausibly Machiavellian, not inhuman, though oiled with hubris. He’d so much prefer compromise that he hatches one at the last minute. Bennett shows Cromwell’s real scorn is contempt for inferiors: brushing off the foolish Duke of Norfolk, using Rich like a rug, twisting Archbishop Cranmer, even pressing the Common Man into service.

Asif Khan’s parodic Signor Capuys is amusing, rather thickly-accented in a French double-act with Hari Kang’s Attendant, like two religious caterpillars to the Spanish king, despite being French. Sam Parks makes Archbishop Thomas Cranmer sound reasonable as if condemning is a matter of bad taste. Indeed his mildness exudes a shiver of self-preservation.

1960 still allowed parts of extreme brevity where now multi-roling or excision might be the norm. Louisa Sexton’s Woman is a vexatious litigant whose mischief riffles through the plot, but who herself explodes with bitter words; whom Sexton renders acid-tongued, voluble and sour. Sexton suggests wounded self-delusion utterly unforgiving even at the end. Even so, More has words for her. Huw Brentnall’s sole ensemble part is the one Bolt oddly found no words for.

A gleaming silver-sterling revival in Church’s hands, it runs for two hours 40, slightly longer than billed, though will probably quicken. For a first-class revival, tightly written and perennial, it won’t be bettered for many years. If it’s drama you’d enjoy before the holidays, make it this one. A must-see, one of the very finest plays to have reached the theatre this year.

Associate Director Sydney Stevenson, Casting Director Gabrielle Dawes CDG

Production Manager Andy Pye, Costume Supervisor Karen Large, Props Tegan Cutts for Lisa Buckley.

CSM Eric Lumsden, DSM Lara Mattison ASM Cat Simpson, Wigs and Wardrobe Manager Jason Cook, Wigs and Wardrobe Manager Debbie Bennett.

Eward Bennett and Asif Khan. Photo Credit: Simon Annan