Review by Simon Jenner, September 1 2025

★★★★★

Last night’s production with BBC and ENO forces conducted by John Storgards and directed by Ruth Knight is a one-off production, not an opera-house transfer. In the best sense it’s special, and tailored for the Albert Hall.

This was the opera that made and marred Shostakovich the great opera composer. The Lady Macbeth of the Mtsesnk District (the original story by Nikolai Leskov, from 1863) is the greatest Russian or Soviet opera of the 20th century. Shostakovich wrote it 1930-32, in his early-to-mid-twenties. The libretto’s by himself along with Alexander Preys his librettist for his comic one-actor The Nose. It was to have been the first of four, just to start with: The Women’s Ring Cycle from different periods of Russian/Soviet history. Portraying the eponymous character as a passionate, resourceful yet sensitive victim, not simply a cold-hearted triple (originally quadruple) murderer, Shostakovich probed women’s oppression and struck a huge nerve. An enormous success it ran for two years, until…

Amanda Majeski. Photo Credit: Acosta

Stalin’s infamous Pravda article appeared in January 1936: ‘Muddle instead of music… this could end badly.’ The opera abruptly vanished (as did Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 4 in rehearsals) and Shostakovich was on notice. His Symphony No. 5 was his response. Lady Macbeth was only reinstated in a tamer version (it had already been tamed by 1936, before its rehabilitation in 1958). With this, and despite Shostakovich trying to write other operas (notably Dostoevsky’s The Gamblers) he never managed it.

It’s taken many years, first to be restored as Shostakovich wished, to its original version (for the 1978 Rostropovich recording). Then after even the British press originally had attacked it in 1936, to enter the repertoire. Storgards marshals – sometimes just for brief moments – the BBC Singers, ENO Chorus and notably Brass section with the BBC Philharmonic,

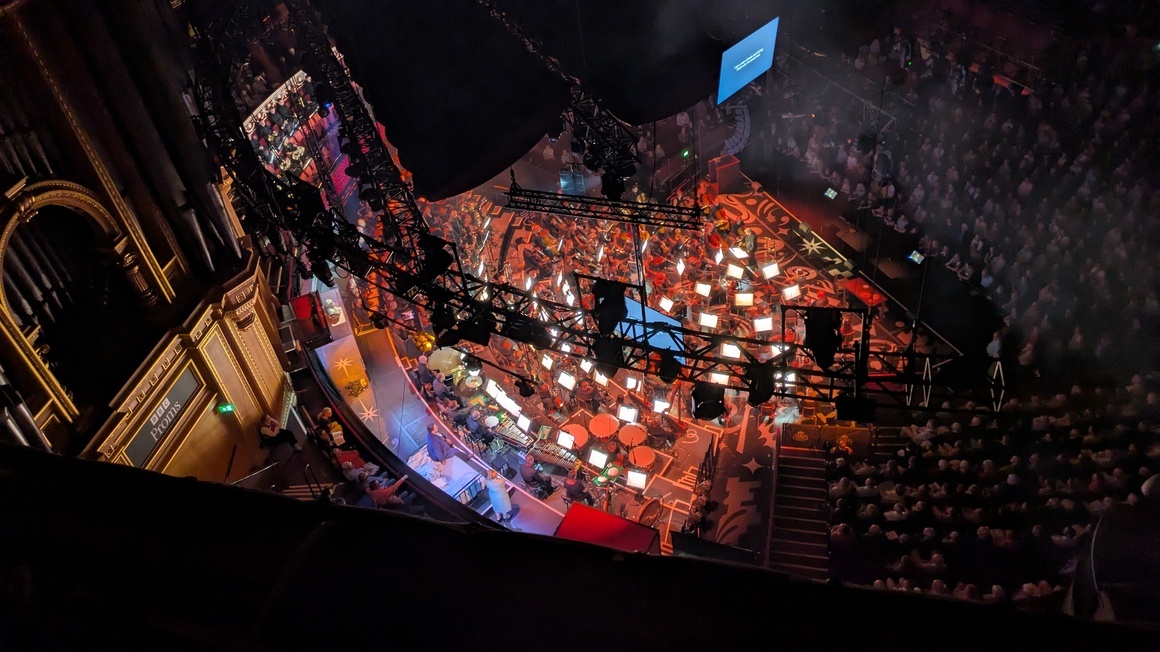

Ruth Knight’s semi-staging is stark but not ineffective for a tale where the lover sexually molests one woman which leads to his seducing of another through a bout of wrestling. And several murders . Seeing it depends where you are. At the back (invisible to some) lurks an iron bed and a box that lit up red at inflamed moments. This means characters often sidle through the orchestra for scenes. There’s a small table, and jutting downstage a wooden witness box. It’s the lighting that tells the story in almost cartoonish strokes, pitilessly spotlighting characters (mainly Katerina, the heroine sung with nailing passion vehemence and melancholy by Amanda Majeski). The curve of digital screens behind the performers switches colours: several times to blinding white, transforming the Chorus of English National Opera. Sometimes they’re a melancholy convict or workers’ chorus, sometimes celebrating a wedding, quite often a baying mob (that’s where the white cartoons them). The coding isn’t always clear: the entire stage was drenched in red not just for sex and violence but drama. A bluish teal-turquoise suggested midnight or at least a distraction from the red shift.

The orchestra’s notable not just for the brass but the huge percussion, and you realise quickly how close we are to Shostakovich’s early film and theatre music with madcap Keystone Cops moments (and there are some in Act Three). This gleeful satirical edge and satiric flaying characters are put through, contrasts with supreme lyrical moments: moments that presage both the snarling Symphony No, 4 but also more lyrical, desperate moments from later Shostakovich. This is a score at a crossroads and what might have been is achingly prefigured. There’s repetitious music, and parts that deliberately hang fire; and a surprising amount of pure orchestral music, enough for a symphonic suite. Some of these are amongst the finest parts of the score.

Majeski is riveting and commands throughout, as she has to, with the score allowing for almost hushed accompaniment as Katerina so often contemplates her bleak lack of options. The Hall’s single-level staging, where only the chorus is elevated, poses huge challenges for modern operas (baroque ones fare better). Nevertheless Storgards somehow both keeps the orchestra at full throttle yet leaves moments for the soloists to breathe. It’s still a challenge and the giant monitors reproducing the text (it’s sung in English) can’t be seen by many people in higher tiers, or some lower down. They need a couple more at least.

There’s ardent, cut-through and deliberately sugary singing from Nicky Spence. And some relief for the audience: As his Sergey muttered “Now we’re really in the shit” a guffaw rippled round. Brindley Sherratt as Boris was vocally the clearest of the evening: rich as bitter poisoned chocolate, a proto-Dostoevsky patriarch of pure spite and lust. Boris wants Katerina too, hence his watchful jealousy. As Boris’s son, Katerina’s husband Zinovy, John Findon might be impotent in bed but outside he’s more than a drip off the old block. Despite the wilting trombones he’s vicious. Findon had both the vocal cut-through and burly presence. He’s no wimp.

Ava Dodd’s sexually harassed Aksinya and Convict, and Niamh O’Sullivan’s sexy but also vicious Sonyetka are both characterful: by turns angry and slinky then gloatingly nasty. Sir Willard White got an extra cheer for his rich-toned Old Convict who held together a snaking and vanishing chorus at the end. Thomas Mole’s Mill Hand but especially baritonal Priest were notable, as was Police Sergeant Chuma Sijequa, a parodic baritone duetting with the drunken Shabby Peasant of tenor Ronald Simm a small virtuoso performance. William Morgan’s Teacher darts his voice over a clump of baritones at one point, including Alaric Green’s fine-bored baritone Steward. Much detail is lavished on the singing, though in truth on this stage some is lost.

The night belongs to Majeski, centre-stage almost throughout, bar that Keystone Cops interlude. Her interactions with Spence are memorable though passionate, bitter, desperately tender. Spence brings a debased heldentenor to his role, adding saccharine so his magnificence slurs into insincerity. Everything’s stripped away from Katerina, even dignity. A woman who started as “so bored I could hang myself” has had that hopelessness turned inside-out by sexual passion. So Majeski’s voice feels at the end a passion so powerful it annihilates itself. An extraordinarily moving Prom, and along with Shostakovich’s 13th Symphony on August 15th, the pinnacle of the various anniversaries this year. Now to see the opera revived

Photo Credit: Simon Jenner