Emma D’Arcy Photo Credit: Camilla Greenwood

Simon Jenner May 31st 2024

“Suppose I were to begin by saying that I had fallen in love with a colour.” One sentence. Three actors speak it. Maggie Nelson’s 2009 prose work Bluets is dramatized as a Live Cinema-cum-theatre performance by Margaret Perry and directed by Katie Mitchell at the Royal Court Jerwood Theatre Downstairs, till June 29th.

Directed is too mild a word for Mitchell’s technique, pioneered with her production of The Waves in 2006. Nevertheless dramatizing such a work – whose only theatricality lies in fillets of images – demands it. The Court’s artistic director David Byrne declares his first production of this space embraces this “thrilling and unmissable proposition” to present something ground-breaking. Bluets, originally a book of 240 Blaise Pascal-like propositions, certainly answers that.

Bluets is indeed prefaced by a quotation from Pascal’s Pensées, about all philosophy not being worth an hour of pain. Nelson wryly intimates that Autotheory, the intersection of memoir as self-exploration via critical theory, isn’t so new. So an unclassifiable artform is here treated to a revolutionary intersection of theatre and film.

Two strands, the loss of Nelson’s ex-lover, the “prince of blue”, and terrible injuries her friend sustains, with her three-year rehabilitation, span Bluets. It’s covered here in 75 minutes.

A lifelong obsession though is with the colour blue. Not quite blues, but a complex of depression, divinity and desire – sometimes occasioning laughter. Viagra, Nelson informs us, lends a blue tinge to colour perception.

Originally developed at Deutsches Schauspielhaus Hamburg, the least complicated part of this hybrid is that Bluets is performed by three actors: Emma D’Arcy (House of the Dragon), Kayla Meikle(ear for eye) and Ben Whishaw.

Though each represent a subtly different state of mind – quotidian, experiential, objective – such states are too porous for actors to sustain functional identity. Spoken lines – or paragraphs – fragment between them. There’s also a voiceover subverting this subjective equilibrium.

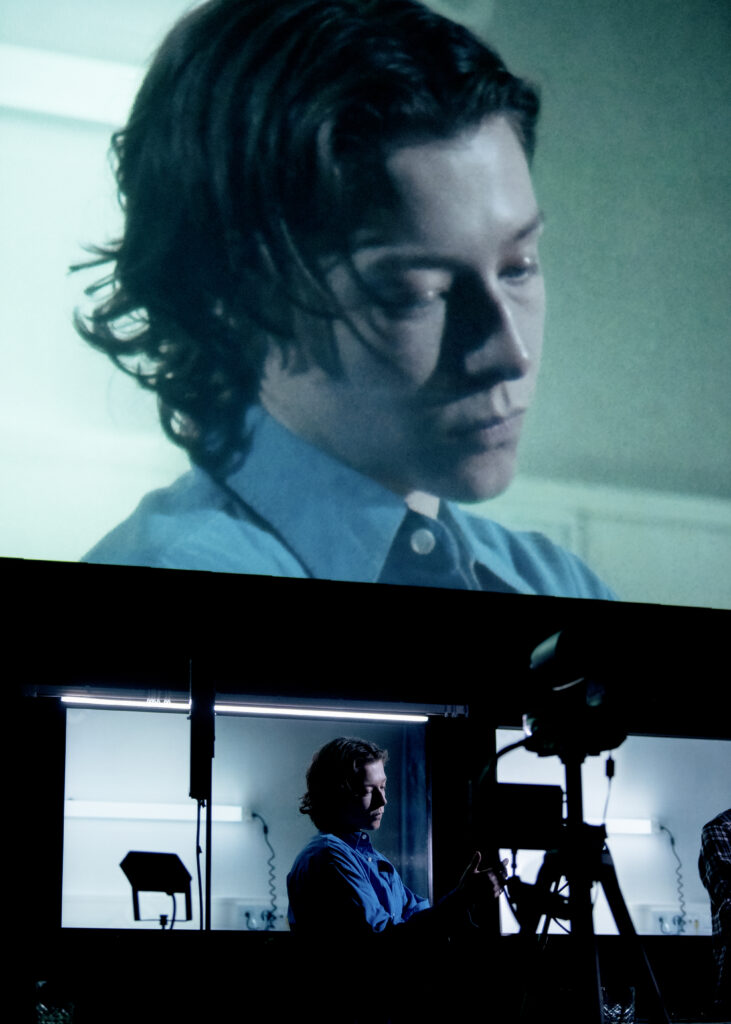

The process of developing pre-shot film streamed to live acting and sound is set out by several creatives. Alex Eales’ set in the Downstairs includes three cameras with video backdrops, and a large screen above, whose default is blue. Indeed Nelson cites Derek Jarman’s valedictory 1993 Blue.

Video designer Ellie Thompson crafts a hierarchy of screens feeding the large one above it; live/pre-filmed footage is chosen in uneven rotation. Thoroughly anglicising California-based Nelson’s experience, video director Grant Gee has shot much material onto which, via camera, actors are projected onto the backdrop. London high-streets, Southwark Bridge or Western Road Hove and the burnt-out West Pier are sequenced: a narrative strand of seaside blue.

Actors ruminate on the beach: there’s a mix of pre-shot and mapped, sometimes phasing out of synch, as the main screen switches between. Blue as pigment provokes sensual images: “you might want to rouge your nipples with it” murmurs Wishaw. There’s repeated swimming-pool immersions on-screen.

Lighting designer Anthony Doran sculpts tenebrous night-effects as D’Arcy and Meikle grasp a pillow and sheet. There’s constant deconstruction, just below, of the illusion above.

Singers from Billy Holliday to Joni Mitchell and Emmylou Harris trace Nelson’s own blues though music. Sound designer Paul Clark, working with co-sound designer Munotida Chinyanga, conjure a five-part “symphony” of sustained musicality. It isn’t easy to pick out distinct movements. At other times a monitor beep drips pain like reversed morphine, as the triple-acted Nelson visits her quadriplegic friend.

Nelson (via D’Arcy and Meikle) quotes Simone Weil: though Bluets bears uncanny resemblance to Fernando Pessoa’s Book of Disquiet. Even closer, Cyril Connolly’s 1944 The Unquiet Grave excavates depression through literature. Taking place over a year it laments a lover’s loss.

Nelson’s primarily a poet. Bluet is both flower and invocation, quintessentially American. The word alludes to Hart Crane’s innovative use of the word in his 1923 poem ‘For the Marriage of Faustus and Helen’: “Inevitable, the body of the world/Weeps in inventive dust for the hiatus/That winks above it, bluet in your breasts.” Less familiar to British readers, those last four words embody the essence of Bluets.

Comically, when the poem was first printed “bluets” was mistranslated to “blues”. That comedic tension, like blue things Nelson assembles to bleach out on a shelf, is wryly translated too.

Perry writes of how first she, then Mitchell filleted Bluets’ thickets of allusion. Goethe’s theory of colours repeatedly emerges here. His 1774 Sorrows of Young Werther, the protagonist shooting himself in his blue overcoat, survives too. It brings irreverently to mind the quatrain about him borne on a shutter, whilst Charlotte, being well-bred, went on eating bread and butter.

Ben Whishaw Photo Credit: Camilla Greenwood

Occasionally Nelson cracks jokes; the explosion of audience relief is palpable. Particularly when Nelson relates how she bookshop-browsed a 2001 tome (The Deepest Blue: How Women Face and Overcome Depression), rejected it then ordered it online.

Nelson is more interesting than self-help, as Wishaw, Meikle then D’Arcy proclaim: “Clinical psychology forces everything we call love into the pathological or the delusional or the biologically explicable, that… I don’t know what love is, or, more simply, that I loved a bad man.”

That bad choice is undermined: “How often I’ve imagined the bubble of body and breath you and I made, even though by now I can hardly remember what you look like.” Sexuality’s explored via Catherine Millet’s The Sexual Life of Catherine M, riffled on screen by Wishaw andMeikle. Indeed sex the couple had was one of the two “sweetest sensations I knew on this earth” (the other being love of blue). Explicit sex is pervasive here.

The injured friend’s witness counterpoints hedonism. There’s descriptions of horrific injures, near-perfect reconstruction of her face but continuing paralysis, with repeated shots of D’Arcy’s hand caressing Meikle’s. Quoting her friend’s dismissal of such gems as “what doesn’t destroy you makes you stronger” Nelson’s trenchant solidarity flashes in D’Arcy’s put-down.

Ultimately Bluets tackles the divine, refracted though Pascal, Weil and humour. Meiklesparkles with cool humour before D’Arcy takes it up and Wishaw briefly comes in on the word “pants”: “In this dream an angel came and said: You must spend more time thinking about the divine, and less time imagining unbuttoning the prince of blue’s pants. But what if the prince of blue’s unbuttoned pants are the divine, I pleaded. So be it, she said.”

Meikleand D’Arcy share the epilogue: “Love is not consolation,” Nelson says, citing Weil. “It is light.” Designed as an unrepeatable event, acknowledging that Nelson is reluctant to contemplate such theatrical realisations of her prose, this production fascinates. Its chief virtue though might be to send you to the book.

This review first appeared in Plays International & Europe, to whom grateful acknowledgment is made for reproducing it here.

Emma D’Arcy Photo Credit: Camilla Greenwood