Photo Simon Jenner

Simon Jenner February 8th 2024

Natasha Higdon and Writers Mark Ensemble have sent three months devising an extraordinary homage: Kafka Play directed by Higdon at Fabrica for three performances on 7th and 8th February, is as deadpan s a black-and-white face in Metropolis, and for good reason.

This homage to the writer who died aged short of 41 in 1924 received a centenary homage addressing his lesser-known works. Split between screen, tableaux involving dance and a variety of objects in the Fabrica hall often taken up and used (a small dolls-house of Gregor Samsa’s bedroom designed by Amanda Rosenstein Davidson for instance) it’s also a hommage to black-and-white silent films of the era. Videographer Nick Petrouis projects black-and-white images and elements of film throughout.

Lit by Apollo Videaux to spectral effect – a fine use of electric blues on black/white costumes for instance -it often gives more than the effect of spectral or flickering cinematic light. At its best, with some of the tightest movement, it approaches – and sometimes achieves – the sacramental.

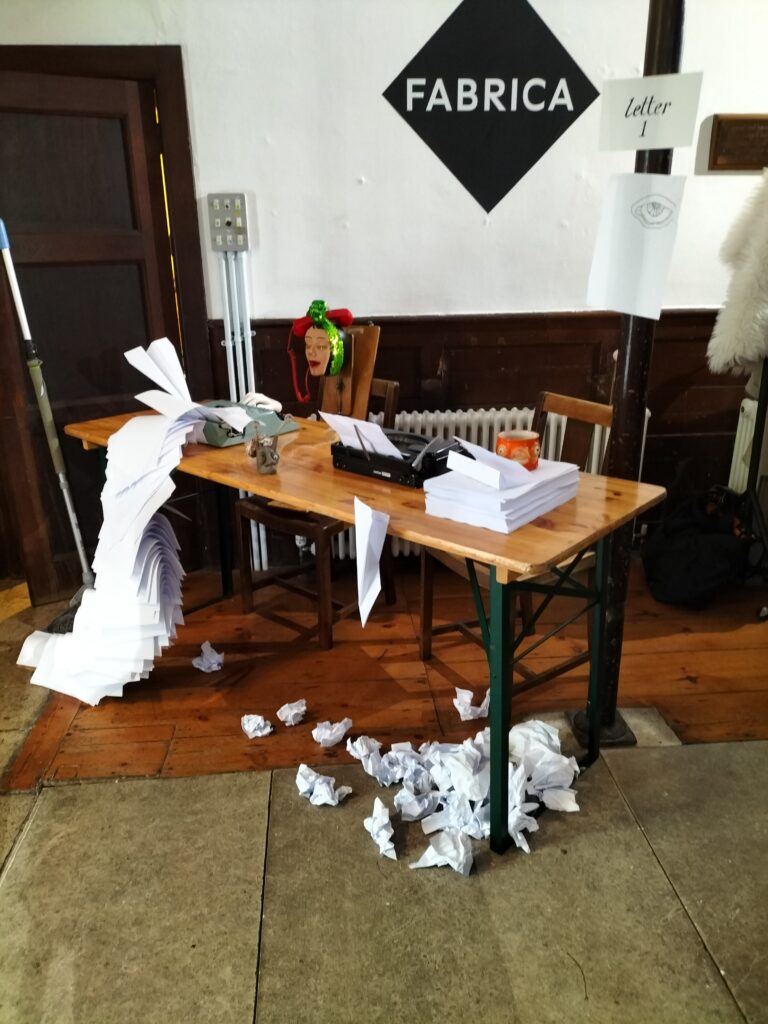

There’s a range of insets, including the fist with a typewriter and scrunched paper at the entrance, alcoves with sacramental objects of occult beauty, the theme of white predominant and with the typewriter, black. The Fabrica’s acoustics are that of a church, throwing up with wood inlays a variety of sonic bounce challenges as well as lighting ones.

I am happy to work. Are you happy to work?

“Do you like work?” performers ask the audience on their willingness to work like a bunch of crazed UC government officials. We know, if we know Kafka at all, where we are. The first tableaux with Samsa’s house is irradiated by five performers: Lorraine Yu, Maya Kihara, Julia Mandler, Nicole Zivolic, Louise Watts. Often to entrancing effect an occult storyline is suggested along lines we might guess. After all, John Abulafia devised a Metamorphosis at Oxford back in 1969, which Steven Berkoff then appropriated – with gratitude as he later noted.

What’s true for this more concrete 15-minute piece even more true of much else. Here, we enjoy a self-contained moment to inure the audience to more abstract elements. As storytelling it wasn’t ideally clear and you start supplying your own narrative: such gestural work needs a pull-through.

Dolls

The most entrancing tableaux followed, a ballet with dolls , based on the tuching true story of Kafka consoling a girl who lsoe her doll in a berlin Park. Despite his efforts, she never found it. But of course the doll becomes transmogrified in the letters. We glean this from the video projection.

Performed with touching grace by Lorraine Yu, Julia Mandler, Nicole Zivolic, it’s a more intimate and affirmative moment. At this point though the story could easily have been narrated, as he silence wall was broken in the previous tableau with the fourt wall following in the audience being questioned. Here, a mode of speech could be developed, almost improvised with an easy litanic delivery if needs. Treading the story is a little distracting. It’s partly meant to invoke silent films of course, but can pull focus.

Contemplation – nine stories from an existing eighteen

By far the longest section were the nine linekd stories told over the second part of the performance. Lasting just on an hour, here paradoxicaly was where the screen projecting a single image cud have come in very useful indeed.

The nie stories arent’ itrated. They could have been projected on the cscreen proor to each tableau and rested for some 20 seconds before the performers entere. As it is, we have no idea what’s being enacted, the conversation becomes one of inner dialogue and workshop conversations between actors who know what they’re projecting for each other. Crucially though these aren’t communicated to the audience, unlike the previous clearly labelled narratives.

There’s a summary in the programme, just a list (people complained the print was small, but it’s clear enough when you get it home: a programme of this length is a wonderful luxury and wholly necessary). For another run Videographer Designer Nick Petrouis might supply simple titles at this point since the projection wasn’t used at all in the major part of the performance, bar a single theatrical image, sepia-tinted and seemingly of a theatre c. 1900.

This matters as there’s such exquisite work on offer. There’s also the challenge of blocking. Some work – the third narrative where actors dance along a line of light Videaux throws down lie a challenge – is beautifully blocked. A fith one where Lorraine Yu dances in a solitary, almost prayer-like manner is equally absorbing and moving.

For the record these comprise Decisions, The Sudden Walk (is this what I took as a the third?), Clothes, The Batchelor’s Misfortune, Rejection, The People Running by, The Merchant, The Street Window, and Excursion into the Mountains.

Alas, the scenarios aren’t very much more illumined by such iteration. But glimpses are possible. Trouble is, whilst watching, you lose sight of them and with the dim lighting wholly necessary, there’s no way you can squint to remind yourself.

In addition to the actors above, Michael Sterrett taking on the role of Kafka’s great friend and executor Max Brod, has to wrestle with the injunction to burn everything, and of course not doing so. If a writer really meant to destroy their works, they’d do so. Using his own accent – one other actor we’ll come to delighted in something other – he iterated the world of Brod and Kafka.

To pick through these would be impossible. The father’s Rejection was however beautifully realised: Kafka’s own father rejecting his son, naturally giving rise to Metamorphosis. Apart from these elements, the final two scenes, involving voicings of Jevon Antoni-Jay in mittel-Europe, were entrancing. All performers were stretched exquisitely here, and Antoni-Jay voicing something out of the silent Metropolis veered from sinister to comedic. I was put in mind of The Fearless Vampire Slayers and “Lady, is this your unlucky day.”

But that’s a moment of levity not intended to guy something remarkable. As the finale tableau bursts forth with an umbrella ballet we’re taken to physical theatre’s storytelling without just a single ingredient needed to render it absolutely clear.

At its best this Kafka work is transcendent, approaching Brooks’ Holy Theatre. There are such moments, and others of great linear beauty, sculpted out of Videaux’ lighting and the chorography Higdon and her team have devised. The ensemble’s large and perhaps a core team might devise something more exquisite.

Certainly there needs to be a re-thinking of how narrative – there needs to be a spine of this – can flourish. This work can’t exist as something abstract as its gestures are too tightly-formed. To let it breathe in the gestural, it must root itself in something specific. As it is, the cut lilies of ambition tend to unfold and drift.

This Kafka needs focusing and tightening, above all clarifying its last ninefold section. It has enormous potential, and its great flashes could easily catch the light of stars.

Fabrica

Directed by Natasha Higdon, Lighting Apollo Videaux

Letters Design 1-9: Zoe Padley, Catherine Whiteoak, Leah Georgiades and John Reddin, Amanda Orazbekova, Amanda Rosenstein Davidson, Mona Ellie, Molly O’Neill, Jo Gabriele Sheppard, Phil Whiting

Videographer Designer Nick Petrouis, Projections Designers Molly O’Neill, John Reddin and Leah Georgiades

Gregor Samsa’s room design Amanda Rosenstein Davidson

Kafka Play

Writers Mark

Fabrica

Till February 8th